YOU DON’T GET TO SAY MY NAME

On the Batman, his ghosts, and what happens if we unmask a love story

Okay! This is like… a somewhat intense diatribe about Batman comics. It might be pretty unhinged! I think it’s coherent-ish, but who knows! And I know! Comic books! You, beloved reader, probably don’t read those, and that’s okay! I think the post is worth sticking around for, though, obviously in part because my ego says it’s good writing, and i worked real hard on it and had a grand ole time doing it. But also because there’s a question here that i think is worth pondering whether or not you read comics. Because, again, you probably don’t read comic books, right? And yet you know about Batman, a character born from that medium, who still does, in fact, primarily exist in that medium. Yet another Batman movie came out this year1 , and you probably saw it. And even if you didn’t, you know about Batman. You know about the pearls scattered in the alley, the oath against killing; you can rattle off a list of his rogues; you know the whole kit and caboodle of the dark knight. You know this, you who have maybe never read a comic book. Isn’t that interesting? Batman first appeared in the pages of comic books more than 80 years ago, and yet we still hang on to him. This comic book character stuck around so strongly in our culture, some thirty years after comic books ceased to have any mainstream relevance. (which is fine, by the way. I love comic books. Obviously.) Why? Part of it is certainly cultural inertia, but I don’t think that’s everything. I think it’s interesting and worthwhile to ask ourselves: What does it mean that we still care about Batman? How does he appear in the cultural imagination? What can our idea of the Batman tell us about our culture? If Batman is a cypher, what is he a cypher for? If he is a mirror, what do we see when we use him to reflect ourselves? I hope to interrogate these questions here, at least a little bit. Plus it’s fun. It’s comic books! They’re fun! Let’s get into it.

In a 2012 interview with Playboy, longtime and legendary Batman writer Grant Morrison said that “gayness is built into Batman.” They continued: “I’m not using gay in the pejorative sense, but Batman is very, very gay. There’s just no denying it. Obviously as a fictional character he’s intended to be heterosexual, but the basis of the whole concept is utterly gay.” It is not difficult to see what Morrison means2. There is something deeply queer about the “whole concept” of Batman. Here is a man who lives two lives: One public-facing, acceptably heteronormative, vapid, meant for consumption, and, above all, false. The other furtive, masked, drenched in latex and leather; a life by night, noble, secret, a life which bucks the system, a life that is, above all, true. Though Morrison is themselves queer, I do not think it takes a queer person to engage with this reading. What’s interesting to me, however, is how the various writers and artists of Batman media engage with this idea—or rather, these TWO ideas, the first being that the IDEA of Batman is inherently queer; the second being that, for whatever reason, the CHARACTER himself is not—or, maybe, is not allowed to be. In his recent run on Batman, writer James Tynion IV explores the tension between these two concepts through his creation of a new character: The Ghost-Maker.

Basically, I’m here because I need to write about the Ghost-Maker thing. I just need to. So, Batman (Vol 4), Issues 102-105, written by James Tynion, penciled by Carlo Pagulayan, inked by Danny Miki with additional art by Carlos D’Andra3. The four-issue arc is titled “Ghost Stories,” and it tells, fittingly, the story of the Ghost-Maker, a figure from Batman’s past—actually, more accurately, from Bruce Wayne’s, but we’ll get there. In the arc, a mysterious figure comes to Gotham and starts stepping all over Batman’s territory, leaving signals, prematurely solving his cases. We learn that this new vigilante is a man called Ghost-Maker, a lethal crime fighter with skills that measure up to Batman’s own, and for good reason; we find out throughout the arc that Ghost-Maker is an old friend-rival-ally-enemy that Bruce encountered on his world travels as a teen and early-twenty-something, the ones in which he learned the skills he needed to learn to become the Batman. The man who would become the Ghost-Maker was on a similar path, though apparently with different reasoning—where the ever-emotional Bruce seeks to fight crime as a result of the trauma of witnessing his parents’ murder, the Ghost-Maker, who claims he is a psychopath, is in it for the “sheer art” of crime fighting. Ghost-Maker, the man himself tells Bruce (and the audience), Does Not Care. This difference in motivation destroys the friendship; years later, in the comic’s present timeline, Ghost-Maker comes to Gotham City to prove he’s better than Bruce.

I am going to argue that this arc is a an example of a queer author writing a queer-coded story for a queer audience. This fact seems to me so obvious that it’s immaterial to even try and justify this project; I mean, everything I’m going to analyze in whatever-the-fuck piece of my brain I’m typing right now should hopefully convince you. But, for some background: James Tynion IV is a queer writer, he writes queer characters often, especially in his creator-owned comics (creator-owned= comics with no legacy characters whose premises were created by the artists who currently make them), such as in Wynd and The Nice House on the Lake; he writes queers both explicit and coded in the pages of the capes, too, evidenced by, for example, his run on Detective Comics (hey DC, please bring back Dr. Victoria October, she rules).

So. This is a ghost story. This is a love story. This is a story about a love that haunts. Jesus Christ, comic books.

God, where to start. There is so much. There is so much! The opening panel of issue 104, where we see ghost-maker’s gloved hands on Bruce’s naked chest, one holding a needle inserted into Bruce’s skin, suturing a wound Ghost-Maker himself gave, the other just laying there, fingers splayed?

The way Bruce is said to have recounted the story of meeting the ghost-maker to his eldest son/first Robin, Dick Grayson: “It was a lonely road, Dick…until I met a young man. […] we would stay up late, night after night, talking[…] and so, one night, I decided to tell him who I was, and why I was fighting.” (104)? The flashback where Ghost-Maker, masked, clothes billowing, comes across Bruce, shirtless, meditating in the desert, and challenges him to a sword fight, and tells him he’s “vulnerable,” that “caring makes [him] weak”? (103).

I could start in any of those places, honestly, and it’s worth noting that in each of these examples I just semi-randomly pulled, there’s this thread at work—ideas of vulnerability vs lack of vulnerability (I won’t use the word “invulnerable” here, as within the world of DC comics it carries its own history and weight of meanings, though, yeah, Bruce Wayne’s other best friend is literally invulnerable, but queer je ne sais quoi of superman and batman is a whole different essay) by way of disclosure and non-disclosure, clothed and unclothed, masked and unmasked. That’s like the !!! of all of this, and I’ll potentially go back to any of it, but I guess I’ll start at the end, with issue 105, because it’s the one that is the most !!! and not to step too far out of the language of the academy (though I am after all already using it to talk about a gay batman comic) but holy fuck, Tynion! I’m already mentally ill! You absolute king! You madlad!

Batman Vol.4 Issue 105, “Ghost Stories Pt. 4” begins in flashback—"Argentina. Years ago.” It is night, and it is raining. Young Bruce Wayne, carrying a duffle bag, is striding towards a small plane awaiting him on the tarmac. He is going home. He is going home to become what we know he is going to become. And Ghost-Maker is here to try and stop him. He will fail, we know he will fail. I don’t want to use the words “Casablanca vibes,” but it cannot be denied that in our cultural context, this scene is familiar (and not just because of Casablanca). It’s shorthand at this point—the arrival at the airfield. The plane waiting to bear our romantic lead away, and the man who arrives to beg them not to get on it. The rain pelting down on them. I argue, in short, that this is a scenario that the audience (especially the presumed-Western audience implied by a Batman comic) is trained to read as romantic—hell, as endemic to the romance genre. The airport confession scene. A romance cliché. We know this scene. This is a code we already speak.

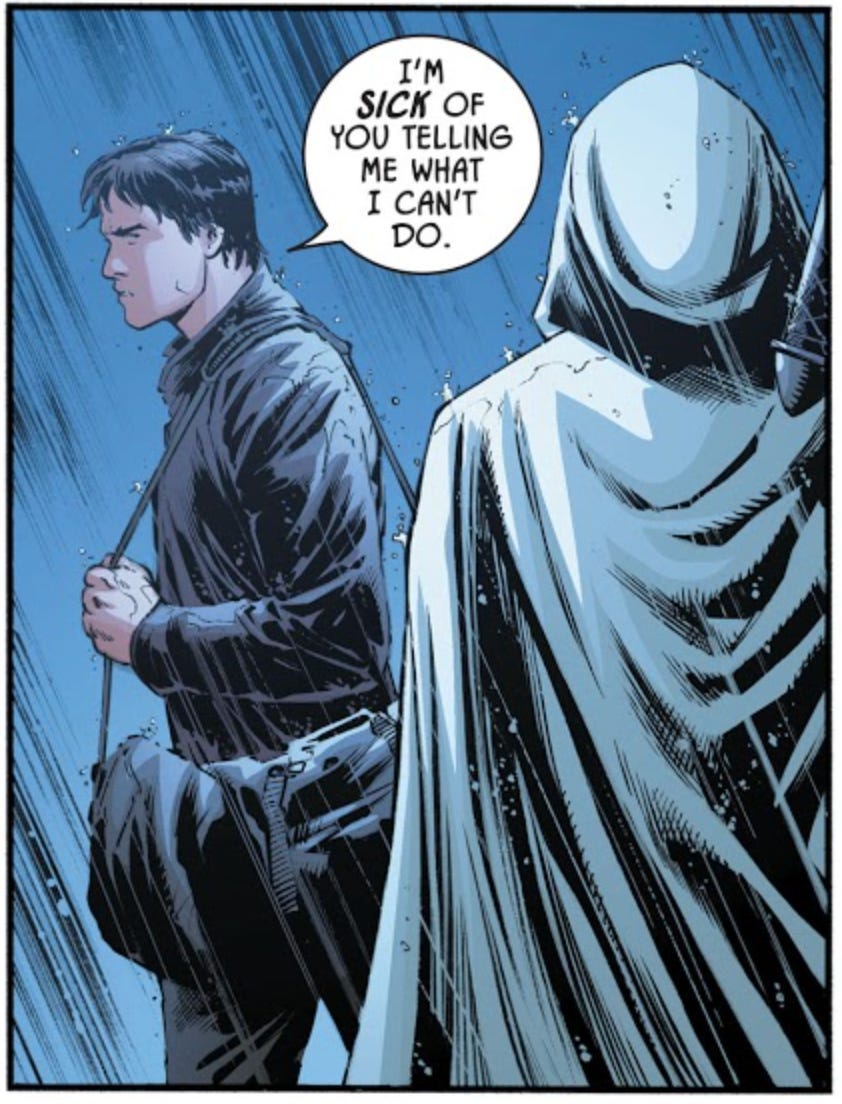

We open on their last meeting before Bruce puts on the cowl. I say puts on the cowl, not just becomes Batman. I’m doing that on purpose, because I want to call attention to all moments of covering and uncovering which occur in these pages, both depicted and implied. Okay, so, Bruce is about to get on the plane. Ghost-Maker is here to stop him. Where Bruce’s face is bare, as are his hands, Ghost-Maker is masked from the nose up and is wearing a hood and gloves. Ghost-Maker confronts Bruce, first accusing him of giving up, and then beginning a plea that we learn Bruce has heard before, as he says, “I’m not interested in hearing this from you again.” The following exchange (slightly edited just for space, emphasis original to the text) takes place across 6 panels; they stand apart in the rain.

I know I need to couch this in textual evidence, and I will, but I just want to say it straight up: This exchange reads like a breakup. We’re already in a context and setting that, as previously established, the audience has been trained to read as romantic. Plus there’s the content of the relationship as described by Ghost-Maker: “stay[ing] up late and night [to] talk;” the implications that Bruce is Ghost-Maker’s problem—his responsibility. And that last line—being told what to do—it certainly renders a familiar picture of a controlling/toxic romantic relationship.4 When he says that last line, Bruce begins to walk away from Ghost-Maker—away from the confession, into the rain, towards the plane waiting to carry him off.

An explosive thing happens in the next panel.

Ghost-Maker grabs Bruce by the arm. The panel is small, just the hand on the arm and one speech balloon, coming from Ghost-Maker: “No. Listen.” He hangs on to Bruce for the next few panels, and keeps trying to convince him: “We’ll start in a small city […] and dismantle its criminal underworld […] and then we’ll go to the next, and the next.” Bruce flatly refuses, Ghost-Maker calls him a coward. In a panel that emphasizes Bruce’s eyes and places Ghost-Maker in shadow, Bruce says “[…] I have no interest in not caring about people […] you’re sick. There’s a part of you that’s broken and you’re angry that it’s not broken in me.” The next panel: Action shot. Ghost-Maker has just punched Bruce in the face. The next panel: Bruce, doubled over, gripping his mouth—because Ghost-Maker has punched him in the mouth specifically, the desperate kiss familiar to the Airport Confession scene transmuted into a thing of violence, but still implied, still gestured to as Bruce reacts to Ghost-Maker’s contact with his lips. Bruce speaks through his pain: “Just leave, Kh—”

Next panel: Ghost-Maker, shouting, framed to highlight how much of his face is covered, just his mouth (his mouth) revealed: “No! You don’t get to say my name again. You don’t get to see my face.”

They part ways, agreeing to never see each other again—Ghost-maker will never come to Gotham, Bruce will leave any city that Ghost-Maker is in.

Okay! Okay! I am so, so interested in that declaration Ghost-Maker makes: “You don’t get to say my name again. You don’t get to see my face.” Like, even leaving aside the similarity that first sentence has to “the love that dare not speak its name,” there is something at play here with intimacy and how it relates to vulnerability. We learn here that for the Ghost-Maker, seeing his uncovered face and knowing his real name are deep, near-untouchable intimacies. Later issues support this claim; in a later issue, a Tynion-penned back-up5 about the Ghost-Maker sees Ghost-Maker immediately after sex with two partners, who are—and this is crucial—a man and a woman. He walks away from them, referring to himself as the Ghost-Maker, and with his face covering firmly in place. This suggests that, for this character, knowledge of his name and face are far, far more intimate than sex. We also know that Bruce has had access to both of these things. By the end of this particular arc (I am once again referring to “Ghost Stories”), the audience is still not privy to these particular intimacies, though they are revealed in later issues, always when he is alone with Bruce. In this moment, however, this moment of breaking where it is revealed that their respective missions—the uncaring one and the caring one—are incompatible, those intimacies are retracted.

I want to turn now how this issue—and this entire arc—concludes: with Ghost-Maker challenging Bruce, still shirtless but with the cowl on hiding his face (a look which I say only half-jokingly is reminiscent of the uniform of a leather bar; I say this to flag another potential instance of queer-coding which seems particularly invested in reaching and signaling to a specific audience) to a sword fight, which Bruce refuses.

Bruce holds his shirt in his hands but does not begin put it on until he has convinced Ghost-Maker to stay in Gotham and fight at his side.

Only when ghost-maker agrees does Bruce get dressed; many lovingly detailed panels are devoted to Bruce pulling on that shirt slowly as he talks to ghost-maker, tells ghost-maker to introduce himself to Bruce’s kids, and then they run off to fight crime together as Bruce says to ghost-maker “You’re buying dinner after.” Okay, sorry, summary again. So what?

So what that all of this is happening? So, first of all, the framing is romantic and purposefully so, especially in the issue’s very first and very last panels, the tarmac in the rain, the post-coital and sensually drawn act of dressing; in the middle of the issue, and I can talk about why if you want me to, don’t even have the time to talk about it, Harley Quinn tells the story of her abusive romance with the Joker, and it is obviously set up to intentionally mirror the relationship between Bruce and Ghost-Maker: “He made me think he was a broken person, in the exact way that I thought I was a broken person […] it didn’t feel like anybody could hear me, but he could hear me, and I #$@#@ loved that,” Harley says, drawing an obvious parallel to Ghost-Maker’s claims about him and Bruce staying up all night, talking and understanding each other. She’s talking about this, by the way, for a reason. I won’t get into all the gory details (read the arc! It fucks!), but essentially: the Ghost-Maker has captured Batman and Harley Quinn and has tied them up under Arkham Asylum. He has brought another character with him as well: Clownhunter, another Tynion creation. Clownhunter: He’s a young teenager, real name Bao, whose parents were killed by followers of the Joker, and so has vowed to murder as many clowns as possible (comic books, man! They’re like that!).

It’s a set-up, of course. The Ghost-Maker wants this child to murder Harley Quinn. Why? To prove a point to Bruce: Caring does not matter, only violence and vengeance, the art of crime fighting. Harley asks Bao to give her a moment to plead her own case, and she does, talking to Bao and in front of Bruce and Ghost-Maker about her experiences in this relationship, and how she’s trying to move on from it and build a life where she can help people. Then she waits for Bao to kill her. He doesn’t. Care wins. Ghost-Maker is wrong. Bruce is right. Then Ghost-Maker tries to have himself a little swordfight (a swordfight!) with Bruce, a fight which Bruce rejects in favor of an appeal to his former friend: Stay in Gotham. Fight by my side. Ghost-Maker accepts; hence, the lovingly post-coital panel of Bruce pulling his shirt on I previously discussed.

So that’s there, that’s available to us, this is, as I said, a love story, or, maybe more accurately, this is a romance story, not capital-r Romantic but a romance story with the tropes of romantic and sexual story beats being purposefully deployed so that we may recognize them; the romance is highlighted when the story of an textually romantic/sexual relationship uses the same language as that of the relationship between Bruce and Ghost-Maker, so okay, that framing is there, is all I’m going to do talk about the fact that this queer-coded story is queer-coded? So what?

More questions, different but the same: So what’s going on here with care and not care and covered and uncovered? I’m thinking about how the explicit conflict between these characters can be summarized by one of them cares about others, and that makes him vulnerable, maybe, and one does not care about others, and that makes him strong, maybe. Of course, that false binary created by Ghost-Maker is collapsed by Tynion: Ghost-Maker has not successfully killed Bruce, despite Bruce’s extreme emotionality, care, and kindness. And Ghost-Maker also clearly cares, to a certain extent, about Bruce—cares enough to prove him wrong, and more importantly, cares enough to ban Bruce from seeing his face or saying his full name, at least within the pages of this particular arc; in later issues we see a. further intimacy between these two men, including Bruce sparring with an unmasked Ghost-Maker while they discuss details of the case.

(Further moments of intimacy: a few issues later, Bruce’s mind is compromised, and, using some experimental technology (comic books!), he invites Ghost-Maker inside his mind. Inside. His mind. Revealing all. Further intimacy: In the Batman 2021 annual, we see, finally, the truth of Ghost-Maker’s backstory, which he is attempting to obfuscate while telling a tale of glory in battle to Bruce. We, the audience, learn his name: Minkhoa Khan. On the final page, Bruce seems to notice that Ghost-Maker’s story implies a level of care he is hiding. He tries to call his friend out on this, but Khoa refuses to engage. When he tries to bring Ghost-Maker’s care to the fore, we finally hear the rest of the utterance Ghost-Maker had so thoroughly cut off in the past. Alone together entreats Ghost-Maker with a nickname, “Khoa.” This is the show of intimacy which causes Khoa to snap back, demand a conflict instead.)

The one who cares, who is vulnerable, who shows his naked chest, who seduces his old friend to the side of the light, whose cowl, in the final fight of the arc (and, you know, always) reveals his mouth—that’s batman. That’s the batman, that 80 year old cultural icon and cypher of American masculinity. The one who, over the course of every flashback, becomes more and more clothed, who fights, at the end, in a mask that hides his head completely, who is seduced, is Ghost-Maker.

Here, I am going to put forth a theory, which I think is true: The batman which exists within our cultural consciousness is not the Batman who, generally, exists in comic books. In the comic books, Bruce is brooding, grumpy, angry, angry, angry, yes. He is also profoundly loving and caring. He believes in restorative justice and second chances. He doesn’t work alone. (never forget: Robin hit the pages of Detective Comics only months after Batman did.)

Now, comic-book accuracy is not the point; there have been at least as many Batmans as there have been people who write him; dozens, hundreds. My point is that the version of Batman which exists in general discourse is one which affirms a very specific kind of masculinity. Batman is the angry one, the brutal one, the gritty one. He works alone. He puts people in body casts. Keaton’s Batman kills. Bale’s Batman beats up imitators in hockey pads. Batman is the one who broods. Batman is cool, and brutal, and he works alone. Batman is about masculinity is about violence is about toughness is about fear. So here’s one thing I think is going on here. In ghost-maker, Tynion constructs a kind of a version of batman that embodies what batman embodies in the popular consciousness, the popular/pop-culture idea of batman—violent, cold, brutal, egomaniacal, uncaring; he takes this version of batman and projects it onto a character who intentionally presents himself as fundamentally ideologically opposed to batman; he presents himself as very specifically the opposite of batman as he was constructed by Bruce Wayne. So Tynion sets him in opposition to Bruce and then collapses that binary through the power of care, of friendship, of Being Gay as Hell For Your Friend—even if you can’t say that part out loud.

But that’s the other thing, right? There is an implicit question posed by the character of Ghost-Maker, and by the Batman himself, these masked men: What has to be covered? What has to stay unsaid? Why? For those who aren’t in the know, our contemporary comics moment is actually a relatively queer one, especially for DC comics specifically. It’s not just Ghost-Maker’s on-the-page queerness. There’s a queer Aquaman now! (Though not Arthur Curry.) There’s a queer Superman now! (Though not Clark Kent). There’s a queer Robin now! (Though not a queer Batman.)

Let me say it again: There’s a queer Aquaman. Not the original, a different one. There’s a queer Superman. Not the original, a different one. There’s a queer Robin now, but not a queer Batman. Never that.6

In this apparent queer golden age of superhero comics, there are still some love stories which must remain on the level of subtext and coding. The Ghost Stories arc seems to implicitly ask: why must some queer stories remain covered and submerged in queer coding and subtext, while others are brought to the level of text? By repeatedly emphasizing themes of covering and uncovering—with masks, capes, gloves, words—as they connect with care, love, and masculinity—particularly the kind of masculinity connected to and perpetuated by Batman as he exists in the cultural consciousness—Tynion and the book’s other artists call attention not just to this coded narrative, but to the very FACT of its coding. Otherness, covering, vulnerability, marginalization. The fact that we can only use these queer characters to tell queer stories if we continue to cover the story. Because Ghost-Maker is queer, both metaphorically and literally, textually. He is queer, and he is also the collapsed version of the hyper-violent lone wolf masculine ideal notion of Batman.

Because what would happen if we uncovered the gayness built in to Batman? What would happen if we said this name? What would happen if, my god, Batman kissed a man? Would the very idea of masculinity crumble to bits under our feet? What would we lose?

Is what we’d lose even worth preserving?

Ghost-Maker’s problem with Batman is that he makes himself vulnerable. At their final confrontation, Ghost-Maker is armored, Bruce shirtless. The exposed man proves victorious. Ghost-Maker wants to end their encounter with a fight to the death. Batman ends it with an outstretched hand. Because Ghost-Maker’s problem with Bruce Wayne’s Batman is the fact that he cares. He think caring can’t win. Caring wins. Caring always wins. How much dropping your sword looks like reaching out your bare hand!

Gayness, Grant Morrison argued, was built into the Batman. James Tynion adds: so was care. In this character, by this character—in his leather suit, in his secret life, in his furious, furious love for the world, these two things are intrinsically connected. Bring one to the surface, and the other follows. Maybe we should let it.

and it’s great. 10/10 for wet cat batman. I love that greasy little guy and his eyeliner and his giant t-shirt and his absolute lack of game and his Demonia boots. i want to put him on my pocket. man looks like an anemic sailor boy from a decemberists song. perfect bruce wayne.

That Batman lends himself to a queer reading is not a new take; there’s a history there—of course, there’s the deeply homophobic version originated in that motherfucker Fredric Wertham’s 1954 screed The Seduction of the Innocent; a take which helped lead to the development of the Comics Code Authority (aka Hays Code for funny books!) and which was echoed in the 1990s by SNL’s “Ambiguously Gay Duo;” there’s the sheer fact of how deeply the 1966 Adam West Batman is entwined with our conception of camp. There are, importantly, the generations of queer readers who have identified with the Dark Knight.

Going forward, I’m going to be mainly using “Tynion” to refer to the author of these works, because a. I am mainly, though not entirely, focused on the text itself. 2. while I mainly focus on this one arc created by all of these people, all the other comics i reference have some different members of their creatives teams, though all are written by tynion. all that said, comics are highly collaborative and authorship of them never rests solely with the writer.

in this reading, I’ll read it as “control” and not “domination.” But. I want to just drop in here and say that in later issues of Tynion’s Batman, Bruce does wear a gimp suit. And like… not in the way that people joke around and call the Batsuit a gimp suit. He’s captured by Scarecrow, and Scarecrow puts him in a gimp suit. There’s an o-ring. Just something of note! I fuckin love comics.

(back-up=shorter comic occasionally included with some full length comics)

Jackson Hyde, Jon Kent, Tim Drake: I love you, and I love even more the artists and editors who enable your comic book existences. And yet, and yet, and yet.